[ad_1]

Southwest Economy, Second Quarter 2022

Cryptocurrencies have existed for over 10 years. Since their launch, cryptocurrencies have grown in quantity and market capitalization. Because they rely on decentralized technology that is computationally complex, cryptocurrencies are significant energy consumers. Texas’ power-generating abilities have captured the attention of cryptocurrencies as miners move to the state.

Cryptocurrencies have been around over a decade, with their valuations rising notably, though not always steadily. Cryptocurrencies are a form of digital currency that can serve as a medium of exchange and a store of value, although they lack the backing of any central authority or government.

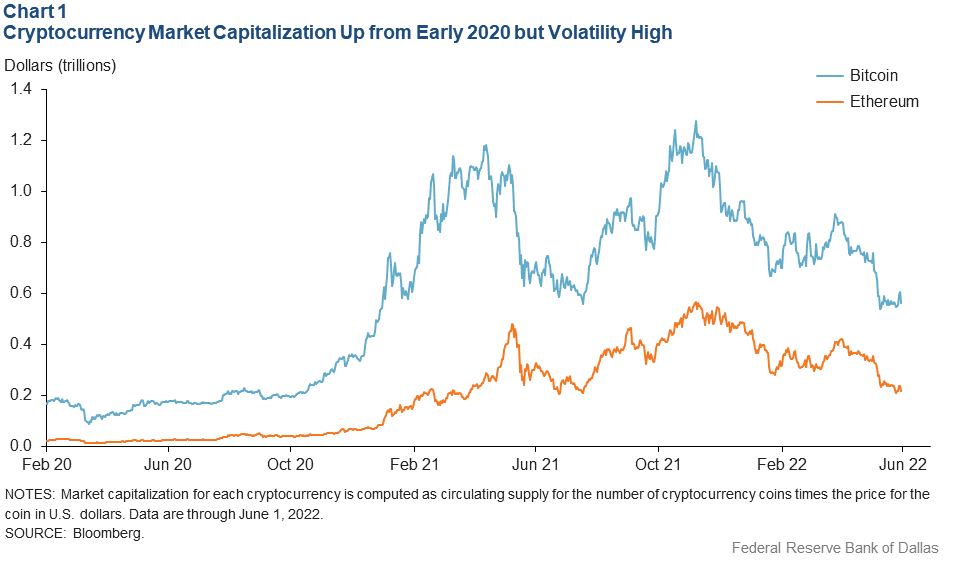

The market capitalization of bitcoin and ethereum—the two largest cryptocurrencies—totaled about $781 billion as of June 1 (Chart 1). All told, there are about 100 significant cryptocurrencies, with a market capitalization of approximately $1.2 trillion, down 60 percent from their recent peak in fall 2021.

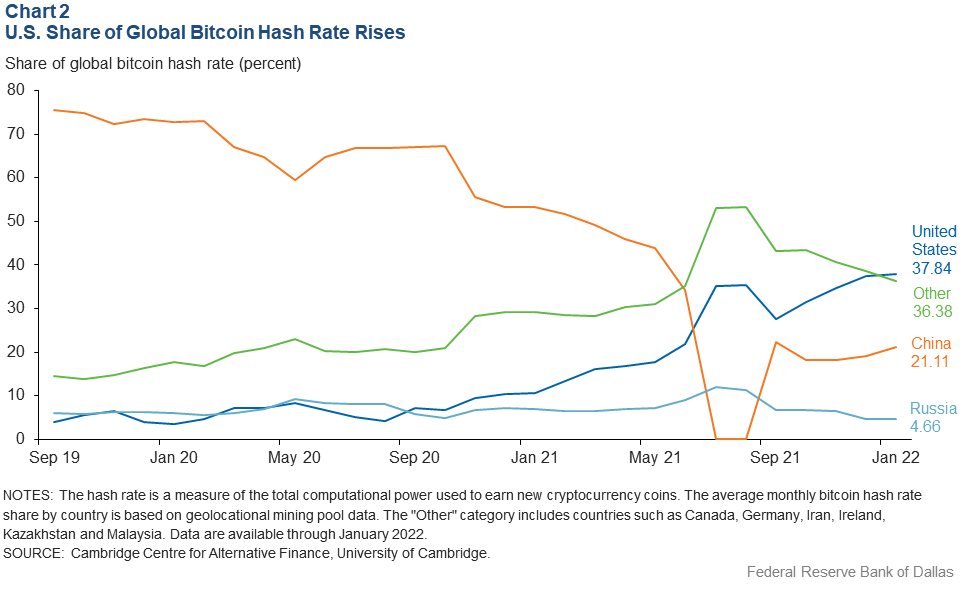

Cryptocurrency mining refers to the work (done by computers) that manages the blockchain, the record of cryptocurrency transactions. Crypto mining is controversial, in part, because the process requires large quantities of electricity, which is often produced using fossil fuels such as natural gas or coal. Moreover, crypto mining is growing quickly in the U.S. and in Texas, following recent adverse regulatory and political developments in foreign centers of crypto mining activity—China, Russia and Kazakhstan.[1]

Mining activity is measured by hash rate—a metric of the computational power needed for calculations to maintain the blockchain and earn new cryptocurrency coins. The bitcoin hash rate plummeted to zero in China in 2021 while rising in the U.S. and other countries (Chart 2).

Although reliable data are hard to come by, some observers suggest Texas may be the largest state for crypto mining, accounting for 25 percent of the U.S. total.[2] Texas’ attraction may be the state’s relatively inexpensive energy and favorable regulations.

A Digital Currency

Cryptocurrencies are supposed to be used like any other currency. But unlike traditional physical currencies such as the dollar, cryptocurrencies only exist electronically.

An individual can hold crypto as a store of value, an investment, and use it as collateral or as a means of payment. Digital coins can be “mined” or purchased on an exchange and stored in a digital wallet.

Transactions in which a cryptocurrency is used are verified and recorded in a distributed public ledger—a database that is spread across a network of computers—the best known of which is blockchain.

Transactions are stored in discrete blocks that taken together form a chain. Each block is a collection of detailed data, such as records or transactions. The blocks are iteratively linked in a chain based on an individual block’s hash value—a calculation based on the data it holds relative to other such links in the chain.

In this process—which also serves as a security measure—the hash value of a previous data block determines the next block’s hash value, which is then used to determine the value of the subsequent block.

There are several reasons for interest in cryptocurrencies. For some crypto enthusiasts, it derives from concern whether fiat currencies—like the U.S. dollar and euro—are a reliable store of value, especially when the Federal Reserve and other central banks have expanded their balance sheets and put significantly more currency in circulation following the Global Financial Crisis in the late 2000s and again during the 2020–21 pandemic.

Hence, some investors not only buy and hold cryptocurrencies because they believe they will increase in value but also because they believe cryptos may act as an inflation hedge, although that hasn’t been the case in the current high-inflation episode.[3] Of course, others worry that with no government backing, cryptocurrencies’ value is not secured by any central authority and could collapse.

An additional appeal of cryptocurrencies is that the blockchain allows immediate encrypted transaction processing and in ways that can include other transaction information, such as contract and counterparty details. This appeals to many consumers and gamers, particularly for those who transact across borders or need real-time payments.

Lastly, blockchain technology allows for greater decentralization of finance because it occurs on a distributed ledger and isn’t controlled by a government. Hence, another appeal of cryptocurrency is the unregulated and anonymous nature of the transactions. However, this feature likely attracts individuals who seek to evade taxes, money-laundering laws or capital controls.

Transaction Costs, Speed

Cryptocurrencies can have high transaction costs and slow speed, and they carry the risk of manipulation. While decentralized finance has the potential to reduce costs and accelerate transactions (relative to traditional financial systems), it doesn’t always deliver.

Transaction costs are volatile and can rise sharply as transaction volume increases. Bitcoin transaction fees were approximately $1.30 per transaction in June 2020, rose to $13.15 by October 2020 and exceeded $60 in April 2021.[4]

A recent study noted that a likely reason for high fees is a lack of competition in cryptocurrency markets, with its authors finding that bitcoin mining capacity is highly concentrated—the top 10 percent of miners control 90 percent of mining capacity. Even more telling, just 0.1 percent of miners account for about 50 percent of mining capacity.[5]

A new payment protocol dubbed “lightning” was added to bitcoin in 2018 to increase speed and reduce transaction costs associated with micropayments.[6] Lightning defers final settlement on the bitcoin blockchain, though that opens a security vulnerability that complicates tracing transactions.

Security concerns center on attacks on the blockchain. A 2020 study analyzed 14 attacks on 13 different cryptocurrencies where the blockchain was manipulated by gaining control over 51 percent of the mining nodes—computers searching for new pieces of cryptocurrency—to undermine the blockchain’s integrity.[7]

Keys to Crypto Mining

Cryptocurrency mining is the term describing the computers that approve blocks of transactions to become part of the blockchain. As compensation for maintaining the blockchain, miners receive new cryptocurrency.

For example, the compensation for mining one block of the bitcoin blockchain is 6.25 bitcoins, about $30,000 based on the exchange rate as of June 1, 2022.[8] Given that there are about 144 blocks mined every day, miners collectively earn bitcoin worth approximately $27 million daily.[9]

To participate, miners must solve a complicated math problem, referred to as the “proof of work.” Solving this problem is slow and energy intensive, requiring significant amounts of computing power, with no guarantee that the time and energy expenditure will pay off—only the first miner to solve the proof of work earns compensation.

Proof of work is known as a “consensus protocol”—a way in which consensus can be reached on changes to a blockchain. Although the proof-of-work consensus mechanism is largely effective at allowing decentralization, it requires significant electric power.[10]

Critics argue that the process is wasteful; energy could be directed to more productive uses, such as powering homes and businesses.[11]

Energy Economics

Mining and trading of bitcoin consumes an estimated 91 terawatt hours annually, equivalent to the annual national energy consumption of Finland or Jordan.[12] Mining a single block on the bitcoin blockchain consumes about 2,000 kilowatt hours, more power than an average U.S. household consumes in two months.[13]

The historically low cost of electricity in Texas relative to the nation and the state’s rapid growth of renewable energy sources, as well as light regulation, have likely helped attract crypto miners to the region.

What are the implications for Texas’ energy sector? On the one hand, there are concerns that crypto mining power demand can increase energy costs, reduce electricity grid stability and lead to greater carbon emissions.

On the other hand, crypto supporters say it is possible that co-locating cryptocurrency mining with commercial renewable energy generation could mitigate pollution, improve the economics of renewable projects and attract investors.

This argument suggests crypto mining could be a key source of demand for renewable power during periods when electricity demand is low and power output is high and storing the excess electricity in batteries is impractical. Hence, combining crypto mining with renewable projects would provide more consistent, dependable electricity demand that could support renewable project cashflows and improve repayment prospects for windfarms and solar farms, for example.[14]

The relationship between cryptocurrency and energy markets suggests more research about the markets’ relationships may be appropriate. For example, depending on whether the price of bitcoin declines or increases, the payout for mining diminishes or grows, assuming a constant price for electricity. This rate-of-return calculation may affect the willingness of miners to participate. Miner participation determines how quickly new bitcoin comes to the marketplace, affecting its liquidity and value.

Additionally, the amount of mining activity may also prompt additional blockchain transactions, as some miners liquidate part of their crypto earnings to pay for the costs of mining.

The increase in demand for energy attributable to cryptocurrency mining is contingent on the continued use of the proof-of-work consensus protocol. The difficulty of mining new blocks on a proof-of-work blockchain increases as the number of miners rises. As concerns surrounding the energy cost for proof of work have grown, some cryptocurrencies may evolve to less energy-intensive consensus protocols.

Ethereum, the second-largest cryptocurrency, announced plans to convert from proof of work to proof of stake in late 2022. In proof-of-stake protocols, which are less energy intensive, miners serve as a validator in proportion to the amount of the cryptocurrency they control.

Impact on Banks

Texas affirmed in June 2021 that state-chartered banks may offer custody services for virtual currency assets. [15] The state has also said banks can allow virtual currencies as collateral for loans.[16] State officials also appear to be responding to the security challenges of “physically” holding crypto, potential operating difficulties at established crypto exchanges and a desire to provide traditional financial institutions an entrée to providing crypto custody and related services.[17]

Banks seeking to offer crypto services must conduct an assessment—identifying and implementing controls to mitigate risks, including loss of client crypto assets, risk-monitoring capacity, money-laundering concerns and reputational risk.

Still, cryptocurrencies remain a novel development in the financial services ecosystem. As such, they may represent increased risk to the financial sector while simultaneously offering innovation that holds the potential for long-term change.[18]

Notes

- China’s central bank banned all cryptocurrency transactions In September 2021; the Russian central bank proposed banning cryptocurrency in January 2022. While this proposal was pending, the U.S. and European Union took measures in April to sanction Russian entities active in cryptocurrency in light of Russia’s war against Ukraine. In Kazakhstan, domestic energy shortages resulted in a government crackdown on more than 100 unlicensed crypto mining operations.

- “Texas Bitcoin Miners Seek Cheap Power, Land and a Place to Stay,” by Shelly Hagan, Bloomberg, May 4, 2022. Luxor Technologies, a mining platform, estimates that Texas accounts for 25 percent of total U.S. mining activity.

- “Inflation and Cryptocurrencies Revisited: A Time-Scale Analysis,” by Thomas Conlon, Shaen Corbet and Richard J. McGee, Economics Letters, vol. 206, 2021.

- “Fees Per Transaction (USD),” Blockchain.com, accessed June 15, 2022.

- “Blockchain Analysis of the Bitcoin Market,” by Igor Makarov and Antoinette Schoar, National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper no. 29396, October 2021.

- “A Measurement Study of Bitcoin Lightning Network,” by Yuwei Guo, Jinfeng Tong and Chen Feng, July 2019.

- “Cryptocurrency Value and 51% Attacks: Evidence from Event Studies,” Savva Shanaev, Arina Shuraeva, Mikhail Vasenin and Maksim Kuznetsov, The Journal of Alternative Investments, Winter 2020.

- “Cryptocurrency Prices, Charts, Daily Trends, Market Cap and Highlights,” Coinbase, accessed May 27, 2022.

- “What Is Bitcoin Mining?” Bitcoin.com, accessed May 27, 2022.

- It is only largely effective because many miners aggregate their equipment to provide a higher likelihood of calculating the problem first and, thus, earning the compensation. These groups are commonly known as “mining pools.” See note 5.

- One study estimates that 90 percent of the transaction volume on the bitcoin blockchain is an unproductive byproduct of user strategies to impede the tracing of cash flows by moving funds over long chains of multiple addresses. See note 5.

- “Bitcoin Uses More Electricity Than Many Countries. How Is That Possible?” by Jon Huang, Claire O’Neill and Hiroko Tabuchi, New York Times, Sept. 3, 2021.

- “Bitcoin Energy Consumption Index,” Digiconomist, accessed June 6, 2022.

- “Renewable Energy Projects Present Unique Lender Risks, Need for Oversight,” by SungJe Byun and Joe Kneip, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas Dallas Fed Economics, April 12, 2022.

- “Authority of Texas State-Chartered Banks to Provide Virtual Currency Custody Services to Customers,” Texas Department of Banking, June 2021, accessed June 6, 2022.

- Texas House Bill No. 4474, passed June 15, 2021, accessed June 6, 2022.

- “Move Along, Says Coinbase’s Armstrong,” by Phillip Stafford, Financial Times, May 11, 2022.

- “Risk in the Crypto Markets,” speech by Federal Reserve Governor Christopher J. Waller, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, June 3, 2022.

About the Authors

Southwest Economy is published quarterly by the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas. The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas or the Federal Reserve System.

Articles may be reprinted on the condition that the source is credited to the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

Full publication is available online: www.dallasfed.org/research/swe/2022/swe2202.

[ad_2]

Source link