[ad_1]

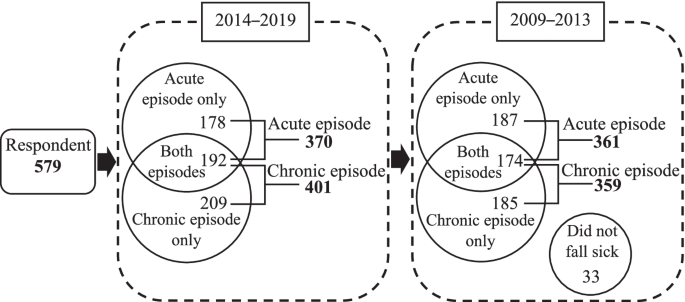

We visited 658 houses, and a total of 582 participants were enrolled in the survey for an 88.44% response rate. Of these, three were excluded, leaving a total study population of 579 respondents. Among the 579 respondents, we obtained 370 respondents who had an acute episode, and 401 respondents had a chronic episode during the of 2014–2019 period. From these numbers, 361 respondents had an acute episode, and 359 respondents had a chronic episode during the of 2009–2013 period (see Fig. 2).

Respondents with acute episodes

Table 1 presents the distribution of health-seeking behaviour that the respondents chose when they had an acute illness; the table is organised by socio-demographic characteristics, before the implementation of UHC (2009–2013) and after the implementation of UHC (2014–2019).

Of respondents with acute episodes before the implementation of UHC, 28.6% chose no medication, 23.8% chose informal care, 34.9% chose a public health facility, and 12.7% chose a private health facility. Age, education, coverage change, and seriousness of the illness were significantly associated with health-seeking behaviour before the implementation of UHC. After the implementation of UHC, the proportion of respondents who chose no medication and informal care decreased to 14.3% and 6.2%, respectively. The proportion of respondents who chose public health facilities and private health facilities increased to 65.4% and 14.1%, respectively. Age, education, marital status, health insurance ownership, type of JKN-KIS membership, coverage change, seriousness of the illness, current health status, and health status change were significantly associated with health-seeking behaviour after the implementation of UHC.

Determinant factors related to change in health-seeking behaviour

Predisposing factors

All predisposing factors examined in this study were significantly associated with changes in health-seeking behaviour by the respondents that experienced acute episodes, except for those who were retired or were never married. It is worth noting, if we look further, among those who were never married, the proportion of respondents who chose no medication increased from 34.8% to 43.5%.

Enabling Factors

Adjusted household income was significantly associated with changes in the health-seeking behaviour of the respondents that experienced acute episodes, except those who had high adjusted household incomes. The type of JKN-KIS membership was also significantly associated with changes in health-seeking behaviour, except for those who were included as non-workers. In the health insurance ownership variable, social insurance was the only factor that had a significant association with changes in health-seeking behaviour. We found that 26 respondents did not have health insurance after the implementation of UHC. Of those, two respondents had lost their coverage, and 24 respondents were never covered by health insurance in either period.

Need factors

All the need factors examined in this study were significantly associated with changes in health-seeking behaviour of the respondents that experienced acute episodes.

Respondents with chronic episodes

Table 2 presents the distribution of health-seeking behaviour that the respondents chose when they had chronic episodes, organised by socio-demographic characteristics, before the implementation of UHC (2009–2013) and after the implementation of UHC (2014–2019).

Of the respondents with chronic episodes before the implementation of UHC, 29.8% chose no medication, 19.2% chose informal care, 33.7% chose a public health facility, and 17.3% chose a private health facility. Age, adjusted household income, health insurance ownership, type of JKN-KIS membership, coverage change, the number of chronic diseases, and current health status were significantly associated with health-seeking behaviour before the implementation of UHC. After the implementation of UHC, the proportion of respondents who chose no medication and informal care decreased to 5.0% and 4.0%, respectively. The proportion of respondents who chose public health facilities and private health facilities increased to 65.8% and 25.2%, respectively. Education, adjusted household income, health insurance ownership, type of JKN-KIS membership, and coverage change were significantly associated with health-seeking behaviour after the implementation of UHC.

Determinant factors related to change in health-seeking behaviour

Predisposing factors

Among the respondents with chronic episodes, all predisposing factors examined in this study were significantly associated with changes in health-seeking behaviour.

Enabling factors

Adjusted household income was significantly associated with changes in the health-seeking behaviour of respondents with chronic episodes. The type of JKN-KIS membership was also significantly associated with changes in health-seeking behaviour, except for those who were not JKN-KIS members. In the health insurance ownership variable, health insurance and social insurance were not significantly associated with changes in health-seeking behaviour. We found that 19 respondents did not have health insurance after the implementation of UHC. Of those, one respondent lost their coverage, and 18 respondents were never covered by health insurance in either period.

Need factors

All the need factors examined in this study were significantly associated with changes in the health-seeking behaviour of the respondents with chronic episode.

Difference in difference estimates

The majority of respondents were female, young adults to middle age, graduated from junior or senior high school, married, had low adjusted household incomes, had a good current health condition, and they thought that they had the same health condition before and after implementation of UHC (see Supplementary Table 2). It was true for those who had health insurance and those who did not have insurance after the implementation of UHC. Regarding the occupation, the majority of those who did not have health insurance after the implementation of UHC were unemployed and those who worked as private employed. In contrast, those who had health insurance after the implementation of UHC were mainly civil servants.

Table 3 describes the results of DID analysis, which determine the effects of the implementation of UHC on respondents’ health seeking behaviour. There were no control variables included in model 1. DID with predisposing, enabling, and need covariates in model 2 was employed to assess the effect of the implementation of UHC on respondents’ health-seeking behaviour. As shown in Table 3, for respondents with an acute episode, the odds ratio of the implementation of UHC was above 1 but not significant statistically in model 1. However, after controlling for the variables of predisposing, enabling, and need in model 2, the odds ratio of the implementation of UHC was above 1 and significant statistically. That is to say, the odds of respondents going to health facilities when they developed an acute episode after the implementation of UHC was 42%, which was higher than before the implementation of UHC (OR = 1.22, p = 0.05, in model 1; AOR = 1.42, p < 0.001, in model 2), which indicated that implementation of UHC had a significantly positive effect on the likelihood of guiding respondents with an acute episode to health facilities for contact. In other words, respondents with acute episodes were significantly more likely to go to health facilities after the implementation of UHC. With regards to respondents with chronic episodes, all the odds ratios of UHC were also above 1 but significant statistically upon both models (AOR = 1.74, p < 0.001, in model 1; AOR = 1.64, p < 0.001, in model 2), which suggested that the effect of the implementation of UHC was significantly positive on the likelihood of guiding respondents with chronic episodes to health facilities for contact.

Table 3 also characterises the association between influence factors and health-seeking behaviour. As observed from Table 3 the odds of respondents with acute and chronic episodes, with very good or excellent current health status, choosing health facilities were 16% and 24.0% lower than residents with fair or poor current health status (AOR = 0.84, p < 0.05; AOR = 0.76, p < 0.015, respectively), which indicated that very good or excellent current health had a significantly negative effect on the probability of guiding respondents with acute or chronic episodes to go to health facilities. Moreover, the likelihood of respondents with acute episodes of somewhat serious illness choosing health facilities were 1.12 times that of respondents with acute episode with no serious illness (AOR = 1.12, p < 0.01), which suggested that respondents with acute episodes of somewhat serious illness were significantly more likely to go to health facilities compared to those with no serious illness. For respondents with chronic episodes, those diagnosed with 2 chronic diseases were significantly more likely to go to health facilities—1.11 times higher than respondents with only 1 chronic disease diagnosis (AOR = 1.11, p < 0.01). For respondents with acute episodes, being in middle adulthood, including wage-earning workers, contribution-assistance recipients, and non-wage-earning workers with JKN-KIS membership, had a positive effect. This indicated that respondents in middle adulthood were significantly more likely to go to health facilities compared to those in early adulthood. JKN-KIS members including wage-earning workers, contribution-assistance recipients, and non-wage-earning workers were significantly more likely to go to health facilities than non-JKN-KIS members. Never being covered by health insurance had a negative effect, which indicated that respondents with acute episodes who were never covered were significantly less likely to go to health facilities compared to those who had always been covered by health insurance. For respondents with chronic episodes, being elderly and having a high adjusted household income had a positive effect, which indicated that elderly respondents were significantly more likely to go to health facilities compared to respondents in early adulthood; and high-income respondents were significantly more likely to go to health facilities than those with low incomes.

[ad_2]

Source link