[ad_1]

skodonnell

Most people judge monetary policy in terms of the level of interest rates. Low rates are easy money and high rates are tight money. More sophisticated pundits suggest that you need to look at the expected path of interest rates over time. If one knew the exact path of interest rates from now to the end of time, wouldn’t that describe the path of monetary policy?

Not really.

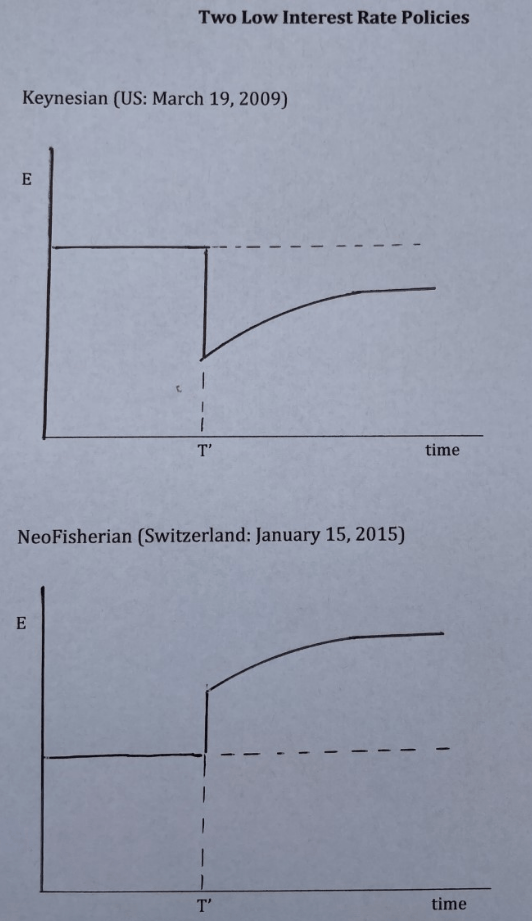

Consider two central banks. Assume that both use exchange rates as the instrument of monetary policy. At time T’, each announces an unexpected change in the path of the (formerly stable) nominal exchange rate (not interest rate) as follows:

Two Low Interest Rate Policies

In the first case, the exchange rate depreciates sharply in the short run and somewhat less so in the long run. It’s an unambiguously expansionary monetary policy. In the second case, the exchange rate appreciates sharply in the short run and even more so in the long run. It’s an unambiguously contractionary monetary policy.

Now, here’s what might surprise you. In both cases, the change in the nominal interest rate is exactly the same from T’ to the end of time. In both cases, short-term nominal interest rates fall and long-run forward interest rates are unchanged. If you think of monetary policy as a path of interest rates, then the two policies are absolutely identical. (This is due to the interest parity condition, which implies that nominal interest rates reflect the expected change in the exchange rate.)

I often see people talk about how a particular monetary policy shock impacted interest rate futures. They might see a rise in the three- or six-month forward Fed funds rate and assume that means that markets interpreted the shock as the Fed intending to tighten monetary policy.

You cannot do that! It’s just wrong. Interest rates do not describe the stance of monetary policy, and they do not describe changes in the stance of monetary policy.

And don’t say, “The monetary policy is the same in both cases above, but there was a non-monetary shock that caused the two macro outcomes to differ.” In this case, the different outcomes is obviously due to differences in the initial change in the exchange rate, but we are assuming the central bank uses the exchange rate as the policy instrument, so one certainly cannot argue that this is a “non-monetary shock”. Indeed, that argument is equivalent to making the equation of interest rates and monetary policy into a tautology. If you define monetary policy as nothing but the path of interest rates, then you will be correct in claiming that monetary policy is nothing but the path of interest rates. And you will have a completely useless model.

Suppose the Fed has been struggling with its control of inflation. Markets view Powell as being too dovish, lacking in credibility. There’s speculation that the Fed will have to raise rates by another 300 basis points to get ahead of the curve, to control inflation. Then Powell makes a forceful statement at a press conference. With anger in his voice, he insists the Fed will do whatever it takes to bring inflation down rapidly, even if it results in recession.

Suddenly, the markets begin to believe he’s serious. Expectations of recession rise sharply. As recession fears mount, the expected future natural rate of interest falls rapidly. If the expected path of the Fed’s interest rates falls less sharply than the expected natural rate, then two things happen:

1. The path of interest rates falls.

2. Monetary policy has become tighter.

Everything Powell does is monetary policy. His votes are monetary policy. His words are monetary policy. The stern tone of his voice is monetary policy – separate from the words. And these words are not monetary policy because they impact the future path of interest rates, or at least not entirely for that reason. They are monetary policy because they also move the expected path of the economy, and hence the expected path of the natural rate of interest. (Think of Powell’s FOMC vote on the interest rate target as the Keynesian part of his policy, and the stern tone of his voice as the NeoFisherian part of his policy.)

I can’t emphasize enough that all this speculation about how high the Fed will need to raise rates is utter nonsense. The path of interest rates is not monetary policy. If the Fed has a credibly effective anti-inflation policy, then it will end up raising rates by much less than if it drifts into a sort of G. William Miller-style passivity.

PS.: These two graphs are not mere theoretical curiosities; they are stylized representation of actual real-world monetary shocks in 2009 and 2015.

PPS.: The central bank of Singapore uses exchange rates as its policy instrument. As (in a sense) do countries on a fixed exchange rate regime, such as Hong Kong and Denmark.

Editor’s Note: The summary bullets for this article were chosen by Seeking Alpha editors.

[ad_2]

Source link