[ad_1]

The Reserve Bank will consider lifting interest rates again today.

Some economists think we’ll see a big rate rise, with more rate hikes to follow in coming months.

But will rapid rates rises cause growth to slow and unemployment to rise? And if they will, what will it mean for the unemployed?

Well, we already use unemployment to dampen inflation. That could provide a clue.

Higher unemployment to stamp out inflation?

This inflation is a global problem and experts everywhere are trying to fix it.

But a few weeks ago, American economist Larry Summers said if US policymakers wanted to get their inflation under control they’d have to allow unemployment to rise significantly in coming years.

He said there were few options available to them.

“We need five years of unemployment above 5 per cent to contain inflation — in other words, we need two years of 7.5 per cent unemployment or five years of 6 per cent unemployment or one year of 10 per cent unemployment,” he said.

It’s not uncommon to hear an economist speak so frankly, and Mr Summers is as mainstream as it gets.

But it was callous.

Through different periods of history, economists like him have often suggested the best “remedy” to kill inflation is higher unemployment.

According to the logic, when you take money away from people they won’t have money to spend, so prices will eventually drop and the economy will re-equilibrate.

But is that the best we can do?

Wouldn’t it be better to target the specific sources of inflation, rather than carpet-bombing the economy with socially destructive “remedies”?

Or is it always necessary to have a little social destruction, with a sharp contraction in spending, to prevent everyone having to experience much worse social destruction later on if high inflation becomes embedded?

Goodbye to the old paradigm

It’s worth remembering where we are.

For the last 40 years, in the neoliberal era, policymakers in advanced economies have been using unemployment to keep a lid on inflation anyway.

And it’s been socially destructive in its own way because it’s led to the emergence of unemployment “scarring” and coincided with the rise of underemployment and growing income and wealth inequality.

Why did they do that?

Because after suffering through stagflation in the 1970s, policymakers wanted to prevent stubbornly high inflation ever becoming a problem again, so they abandoned the post-war policy of “full employment”.

In its place, they started trying to keep just enough “slack” in the economy to prevent serious price pressures returning.

And they decided to maintain that slack by having more unemployed people in the economy than jobs available.

It was a radical departure from the previous way of thinking.

As historian Frank Crowley put it: “The ideal of full employment was lost, possibly forever; and politicians became accustomed to a notion which would once have appalled them — an ‘acceptable level’ of unemployment.”

However, there was clearly a moral problem with the policy.

If the unemployed were going to be used as inflation shock absorbers for the economy, shouldn’t their role have been officially recognised and appropriately compensated?

And shouldn’t policymakers have felt a greater obligation to protect the unemployed who were going to be living under the new, higher-unemployment regime?

Goodbye to the Commonwealth Employment Service

Two important things occurred after that change in policy.

First, after “full employment” was abandoned, the federal government began chiselling away at the institution that supported it.

That institution was the Commonwealth Employment Service (CES).

Since 1946, the CES had been responsible for linking unemployed people with job vacancies, filling labour shortages, and producing regular statistics on the labour force.

It had offices everywhere, with specialist staff that maintained relationships with employers around the country.

Back then, when politicians boasted about finding work for unemployed Australians, it wasn’t rhetoric. They were responsible for the government agency that did so.

Here’s an excerpt from a parliamentary debate in 1963 in which William McMahon, then minister for labour, bragged about his government’s achievements:

“Last year I said during the budget debate that I thought we would have about 75,000 school leavers registering with the Commonwealth Employment Service. It turned out that there were 80,000, and nearly all of them have been found employment.

“A record number of job vacancies was registered with the Department of Labour and National Service during July. We are placing people in jobs at the rate of 7,500 a week.

“Of the eighty-odd thousand young people we had registered with us throughout the year, only 1,300 young men are on our books now, and I have increasing hope that those people, or a large number of them, will be placed in jobs in the weeks that are to come.”

However, when full employment was ditched, the CES was white-anted.

CES staff, who’d spent their careers trying to help unemployed people find work, were increasingly asked to spend more time monitoring the behaviour of the unemployed to help find budget savings by cutting people off welfare for failing numerous “activity tests”.

A new philosophy blew through Canberra, on winds from overseas, that saw value in attaching increasingly onerous conditions to welfare payments.

Initially, there was strong resistance from CES staff to the new culture, but their resistance was worn down.

And things changed fundamentally in 1998 when the “employment services” the CES provided were privatised.

“This radical transformation of employment service delivery is without parallel in OECD countries,” noted the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development in a special paper on Australia’s new labour market experiment.

“Since the introduction of Job Network in 1998, employment services are mainly offered by independent providers from the private and community sector.

“The remaining government body is offering services on the same terms and conditions as the private providers, and has retained only a relatively minor share in the market.”

Fast forward to 2022, and that privatisation has proven very profitable for the private companies that win lucrative government contracts to deliver those “employment services” each year.

But it’s also given those private companies power to suspend Australians’ welfare payments.

An unemployment benefit below the poverty line

Second, even though full employment was discarded long ago, and the government’s “employment services” were privatised, the purchasing power of Australia’s unemployment benefit was also allowed to deteriorate.

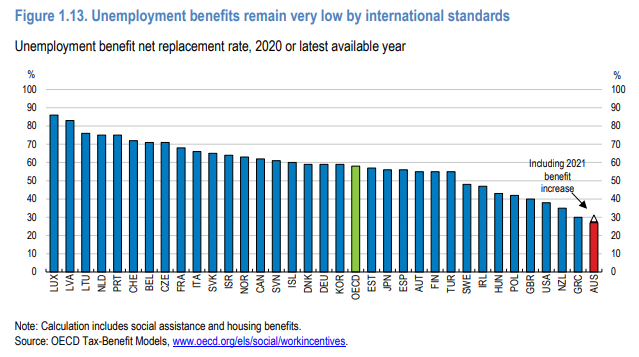

In fact, it’s deteriorated so much since the 1990s that the OECD has called for change.

“The income shock from falling into unemployment in Australia is much larger than in other countries and minimum income supports remain well below the relative poverty line,” the OECD warned in September last year.

“One estimate suggests that 85 per cent of recipients of unemployment benefits will be in poverty.

“The government should further increase the generosity of unemployment benefits and consider indexing further increases to average wage growth,” it said.

And it published the graph below.

What will happen to the unemployed?

The Reserve Bank board will decide today if it wants to lift interest rates again.

RBA governor Philip Lowe says he wants to remove inflation from the system before it becomes embedded.

Officially, he’s said he believes the RBA can achieve that goal without making unemployment rise because the labour market is in such good shape.

For evidence, he’s said there’s still a lot of demand from employers for workers, and households still have hundreds of billions of dollars in savings left over from the stimulus program that should be able to support their spending through the rate rises.

But put that aside for the moment.

The point is that central banks around the world are currently lifting interest rates to try to dampen inflation, knowing it could cause millions of job losses worldwide.

The priority is killing inflation and achieving some price stability.

And in Australia, some economists think the RBA will actually end up lifting rates by so much that the unemployment rate will end up rising above 4.5 per cent by the end of next year, prompting the RBA to have to cut rates again.

So, what will happen to the unemployed in that situation?

Will the people who lose their jobs be treated well by our corporate “employment service providers” or find the unemployment benefit they receive adequate?

This is the system past policymakers have built.

A windfall profits tax?

Finally, there’s always the question of alternatives.

Could there be other ways to combat the current causes of inflation?

One of the main problems for the RBA, in this episode of inflation, is that its emergency-low interest rates led to property prices exploding during the pandemic, which itself was socially destructive.

The RBA says it needs to return rates to more normal levels to stop them distorting asset prices and financial markets further.

But are there other ways to dampen consumer price inflation in these circumstances?

As some economists have noted, oil and gas companies are reaping extraordinary profits from soaring energy prices at the moment, and those soaring prices are hurting household budgets.

How will lifting interest rates push energy prices down?

Richard Denniss from the Australia Institute says a “windfall profits tax” on the gas and coal industry could be used to push down important prices in other areas of the economy, like education or child care.

And that’s just one alternative idea.

It’s worth thinking about others. And their impact on unemployment should be front of mind.

[ad_2]

Source link