[ad_1]

On May 19, the Supreme Court ruled in the case of Union of India vs Mohit Minerals that the recommendations of the Goods and Services Tax, or GST, Council are not binding on the Centre or States.

The landmark judgment, authored by Justice DY Chandrachud, characterises the recommendations of the Council as having “persuasive value” and not mandatory.

The ruling was based on the Supreme Court’s interpretation of the Articles pertaining to the Goods and Service Tax Act introduced into the Constitution in 2016, as well as the balance of power in favour of the Centre in the GST Council.

The Supreme Court rejected the argument that the GST Council’s recommendations are binding on the ground that this would “dislodge the fine balance on which Indian federalism rests”.

Supreme Court judgement on GST sets the stage for a fundental revision of GST implementation and functioning of GST Council from the perspective of cooperative federalism.The Court’s remarks open up the issues of federal flexibilty in determining SGST rates and proceedures.

— Thomas Isaac (@drthomasisaac) May 19, 2022

The ruling comes on the back of a long and varied line of federalism jurisprudence by the Supreme Court. The court’s vision of federalism also articulates a constitutionally-informed alternative to the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party’s “one nation” rhetoric.

What animated this interpretation was the court’s reliance on the federal features of the Constitution, and particularly, the “unique features of federalism” introduced by the 101st amendment that brought in the Goods and Service Tax Act.

Wider federalism jurisprudence

The Supreme Court has been using federalism in constitutional interpretation for over six decades. This interpretive practice received a major fillip when federalism was included in the Constitution’s basic structure in the Kesavananda Bharati vs State of Kerala in 1973. The case pertained to whether Parliament could amend the Constitution.

It was famously used in SR Bommai vs Union of India in 1994, which relied on federalism to interpret Article 356 in a manner that prevented the Centre from misusing its power to impose President’s Rule in States.

While the use of federalism in interpretation has been increasing over time, there has been significant judicial confusion over the nature and extent of this federalism. The Indian Constitution has typically been described as “quasi-federal”, which has had an outsized influence on judicial opinions of Indian federalism.

The Supreme Court judgment on GST brings a new (& realistic)perspective to federalism. A degree of friction between Centre and States is actually good for democracy. Contestation is also a feature of federalism apart from collaboration. https://t.co/oRnWlYRFBr

— Manu Sebastian (@manuvichar) May 20, 2022

More importantly, it has directly and indirectly affected how federal cases have been decided. In several such cases, the Supreme Court has relied on the Constitution’s supposed quasi-federal nature to rule in favour of the Centre, curtailing state powers.

This is unfortunate given the context in which the label emerged and the many ways in which it is now dated. In the formal-legal tradition of the federal analysis that was dominant in the mid-twentieth century, constitutions were compared to the American Constitution – seen as the ideal federal model – and their federal features were labelled accordingly.

But scholarship has long since evolved to recognise that there is no such ideal federal model. Rather, every polity adopts and adapts the essential federal principle of self-rule plus shared rule as per its needs. Besides being conceptually dated, the quasi-federal label also does not take into account the decades of the Indian federal experience that have emerged since the Constitution’s enactment.

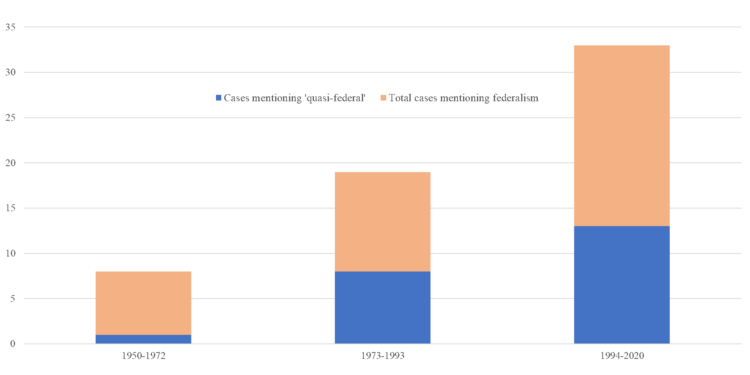

Despite this, quasi-federalism is alive and well in the Supreme Court’s jurisprudence. In a forthcoming book chapter co-authored with Balveer Arora of the Centre for Multilevel Federalism, we found that “quasi-federal” was used in nearly 40% of Supreme Court cases between 1994 and 2020 that referred to federalism:

Against this backdrop, the Supreme Court’s reasoning in the recent judgment is especially remarkable: “The Indian Constitution has sometimes been described as quasi-federal or a Constitution with a ‘centralising drift’ … Merely because a few provisions of the Constitution provide the Union with a greater share of power, the provisions in which the federal units are envisaged to possess equal power cannot be construed in favour of the Union.”

It will be interesting to see if this has an impact on the Supreme Court’s jurisprudence going forward.

How the court ruled

In the ruling on the GST Council, the Supreme Court attempted a harmonious interpretation of Articles 246A and 279A based on its observations regarding the federal features of the Indian Constitution.

The Goods and Service Tax Act was introduced in 2016 through the 101st amendment to the Constitution. The amendment comprised Articles 246A and 279A. Article 246A states that “Parliament, and, subject to clause (2), the Legislature of every State, have power to make laws with respect to goods and services tax” while Article 279A provides for the creation of the GST Council.

Under Article 246A, both the Centre and the States have the power to make laws with respect to Goods and Service Tax. In its judgement, the Supreme Court observed that Article 246A grants “simultaneous” and “equal” law-making powers to the Centre and the states with regards to Goods and Service Tax.

India ushers in ‘One Nation, One Tax’ system.

GST has integrated India into a single common market by replacing the complex, multiple indirect taxes regime with a simple and transparent one.#4yearsofGST pic.twitter.com/pZxBkbRCr5

— BJP (@BJP4India) June 30, 2021

It contrasted this with the sharing of law-making powers over subjects under the Concurrent List, such as education. If any state law on a Concurrent List subject is inconsistent with a central law on the same subject, then the central law will prevail.

This is because of the repugnancy clause, pertaining to legal inconsistency, under Article 254, which the court highlights is conspicuously absent in Article 246A, which covers the Goods and Service Tax Act.

Article 279A provides for the Goods and Service Tax Council, which is chaired by the Union finance minister and comprises a Union minister of state for finance or revenue, as well as state ministers for finance, revenue or taxation.

Under this provision, the Centre’s vote holds a one-third weightage, while the weightage of the vote of all the states combined is two-thirds.

The problem with making GST council decision binding on Centre and States is that it will undermine supremacy of the legislature. SC chooses to make it non-binding to protect legislative supremacy.

— K Venkataramanan (@kv_ramanan) May 20, 2022

However, for a recommendation to be passed by the council, it needs a three-fourths majority. This means no recommendation can be passed without the Centre’s vote, giving it an effective power of veto, which means the balance of power in the GST Council leans heavily towards the Union government.

This being the case, if the Council’s recommendations were to be binding on the states, it would subvert the states’ simultaneous and equal power to legislate over Goods and Service Tax under Article 246A. To avoid this outcome, the Supreme Court held the council’s recommendations to be of persuasive value, and not mandatory.

Alternative to ‘one nation’

The Supreme Court judgement also highlights that states can politically contest the mandates of the Union within the constitutional design. It goes on to observe, “such contestation furthers both the principle of federalism and democracy”, and that “harmonised decision thrives not just on cooperation but also on contestation”.

It places such “contestation” by the states and even “uncooperative federalism” squarely within the framework of Indian federalism. In this light, it views the GST Council as “an important focal point to foster federalism and democracy”.

These observations assume salience in the context of the BJP-led ruling dispensation’s centralising “one nation project”. From “one nation, one tax” to “one nation, one election”, the BJP has been consistently using this rhetoric to frame its centralising policies. It pushes the narrative that only uniformity can achieve harmony and development.

BJP general secretary Bhupender Yadav says ‘one nation one election’ is not just a matter of debate but need of the country, argues frequent polls hamper development works and involve lot of expenditure

— Press Trust of India (@PTI_News) January 6, 2021

In marked contrast, this judgement recognises that disagreement and contestation help further harmony, integration and democracy, and are within the federal framework of the Indian Constitution.

In a sense, the Supreme Court has afforded constitutional legitimacy to the many federal contestations that have emerged over the last few years. However, given the number of pending cases before the court on critical federal issues, it needs to do much more to safeguard Indian federalism.

Kevin James is a Research Associate at the Centre for Social and Economic Progress.

[ad_2]

Source link