[ad_1]

When Hurricane Andrew ripped through southern Florida in 1992, tearing up buildings and killing more than two dozen people, few had witnessed such a destructive natural catastrophe in the United States.

In the 30 years since, the U.S. has endured multiple storms that caused more damage than Andrew, but it was the earlier storm that put insurers and businesses on notice about the potential for such large losses and transformed property underwriting and risk management.

Catastrophe modeling, which was in its infancy before Andrew, became a mainstream underwriting tool; outdated and poorly enforced building codes were upgraded in Florida and elsewhere, making homes and businesses more resilient; eight highly capitalized property catastrophe reinsurers launched in Bermuda, causing reverberations throughout the insurance sector; and insurance contracts were overhauled, effectively imposing much higher retentions on policyholders.

In addition, catastrophe response strategies were rethought and rewritten as businesses and insurers spent more time planning how they would cope with future storms.

Hurricane Andrew made landfall as a Category 5 storm near Homestead, Florida, on Aug. 24, 1992. Previously, it had hit the Bahamas and it went on to cause further damage in Louisiana.

A relatively compact storm, most of its damage in Florida was confined to the area south of Miami. Estimates vary, but according to data collated by the National Hurricane Center, 26 people were killed as a direct result of Andrew; the storm caused $25 billion in total damage; 25,524 homes were destroyed, and 101,241 were damaged. In Homestead and neighboring Florida City, 99%, or 1,167 of 1,176, mobile homes were destroyed.

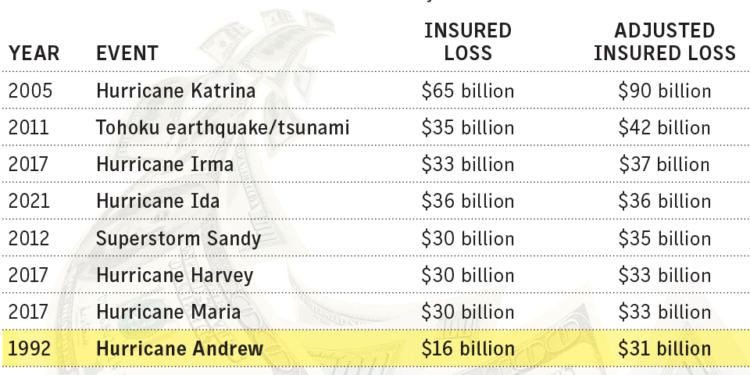

Still, the storm ranks as just the eighth largest insured loss since 1900, causing $16 billion in insured losses at the time of the event (see chart) and does not rank among the Top 10 costliest in terms of economic losses.

Losses covered

While Hurricane Hugo in 1989, which resulted in more than $4 billion in insured losses, had alerted underwriters to the level of devastation a hurricane could cause in the United States, Andrew “caught everybody a little bit off guard in how vast and complete the devastation was where it made landfall,” said Todd Billeter, Stamford, Connecticut-based senior managing director at Aon PLC, who was a property reinsurance underwriter in 1992.

“It had been decades and decades since such a disruptive hurricane had hit Florida,” said Gary Marchitello, chairman of Willis Towers Watson PLC’s North American property practice in New York. “Underwriters immediately recognized they were putting out too much limit and were mispricing the risk.”

Scott Clark, area senior vice president, national risk control, at Arthur J. Gallagher & Co. in Naples, Florida, lost his home during the storm. At the time of Andrew, he was risk and benefits officer at Miami-Dade County Public Schools, a position he retired from in 2016.

The district sustained a $98 million loss as a result of the storm. Most of the loss was insured due to a joint deductible provision for its windstorm coverage, which essentially provided that the lowest windstorm deductible on any of its policies would be applicable for any claims. While the district carried a $1 million windstorm deductible on its excess property policy, its boiler and machinery coverage — placed with a different insurer — had a $100,000 deductible, which under the joint-deductible provision was applied to the property losses, too.

“It was negotiated and was pretty standard in the day,” said Mr. Clark, who is also a past president of the Risk & Insurance Management Society Inc.

Many large insurers had a limited understanding of their exposures prior to Andrew, said Rep Plasencia, executive vice president and Boca Raton, Florida, office lead for Risk Placement Services, a unit of Gallagher.

“The carriers weren’t able to track exposure, like they are now,” he said. “Some of them back then basically tracked their cat loads by pushpins in a map.”

Actuaries based their assessments on historical storms, indexed for exposure growth and increased values, Mr. Plasencia said.

Market changes

The losses from the storm had an immediate effect on the insurance market and the way windstorm risks were underwritten.

Insurers sharply pulled back property limits, Florida risks had to be syndicated in global markets to obtain sufficient coverage and prices increased dramatically, Mr. Marchitello said.

In the year prior to Andrew, Miami-Dade, which was and is the fourth-largest school district in the country based on student enrollment, paid a $770,000 premium for $150 million in property insurance coverage, which was placed with two domestic insurers, Mr. Clark said.

After the storm, the district had to buy coverage from 26 different insurers, predominantly in London, and the premium jumped nearly tenfold to $7.5 million. The windstorm deductible increased tenfold to $10 million.

“At that time, in 1992, the $7.5 million premium was tantamount to the same cost to build an elementary school,” Mr. Clark said.

Many insurers replaced dollar deductibles with percentage deductibles, which increased self-retention by policyholders by multiples, Mr. Marchitello said.

“You took a $500,000 house, which may have had $1,000 or $2,500 deductible on it, all of a sudden if you went to a 5% (windstorm deductible) you went to $25,000,” Mr. Plasencia said.

Percentage deductibles have varied through market cycles over the past 30 years and in the current market some insurers are seeking to impose 10% windstorm deductibles for commercial lines risks, he said.

A big change from a reinsurance underwriting point of view after Hurricane Andrew was a focus on data, said Mr. Billeter of Aon. Prior to the storm, reinsurers would look at spreadsheets and assess insured values within a state, with little information on the location of the properties, he said.

“We were looking at state data, and if you got county level data that would be crazy granular back then,” Mr. Billeter said.

After Andrew, catastrophe models, which had been recently developed, were put to widespread use by reinsurers and later by primary insurers (see related story).

The storm opened up the eyes of reinsurance executives to the extent of losses possible and led to the widespread uptake of catastrophe models in reinsurance underwriting, said Jayant Khadilkar, who worked at catastrophe modeler Applied Insurance Research, which became AIR Worldwide, in 1992, before going on to work at RenaissanceRe Holdings Ltd., TigerRisk Partners and Ariel Re, where he is a board member and adviser.

Prior to Andrew, reinsurers based their underwriting more on market share, comparing a cedent’s premium with the overall industry premium, said Mr. Khadilkar, who is based in Raleigh, North Carolina.

“In the past it was based on historical losses, but with the models underwriters were able to see what potentially could happen,” he said.

The importance of catastrophe models for property reinsurance “can’t be understated,” said Matt Junge, Schaumburg, Illinois-based head of property underwriting, U.S. regional and national, at Swiss Re Ltd. “They drive our pricing for treaties, they drive primary peril pricing as well.”

Claims and mitigation

Andrew also changed the way claims professionals approached catastrophe claims, said Robert O’Brien, a Washington-based managing director in the national property claims group at Marsh LLC.

“Andrew was what changed almost everything about catastrophe response,” he said. “It changed how building codes are reviewed and how they’re enforced, how we mobilize people to get into these areas, and it changed how we track the storms.”

After Andrew it became apparent that local building codes were insufficient and inadequately enforced. In the years following the storm, a commission reviewed the state’s building codes and made a variety of recommendations, which led to the establishment of the Florida Building Code, which supersedes local building codes.

Among the requirements of the code is that buildings should be constructed with windows that are impact-resistant or protected if a building is within one mile of the coast, and roofs must be secured with hurricane ties and straps.

Another big claims lesson from Andrew was making sure insurers and property owners had access to restoration services, Mr. O’Brien said. The breadth of the damage made it difficult to secure and repair properties after the storm.

Risk management practices also changed. Prior to Andrew, property risk control was focused on fire risks, Mr. Marchitello said.

“It became very clear that you could protect against windstorm events, and it brought into focus the quality of construction, the quality of data for underwriters to evaluate risks,” he said.

In addition, for example, organizations focused on securing secondary power sources for businesses that are power dependent, such as food stores and gas stations, Mr. Plasencia of RPS said.

Risk managers also learned lessons in setting up systems to contact employees to ensure they were safe and how to transfer operations to other areas, Mr. Plasencia said.

In addition, risk managers and underwriters began to look more closely at surrounding structures to determine whether they were susceptible to damage from projectiles blown from less well-secured buildings, he said.

“A good property underwriter always pulls up the satellite imagery, and they’re looking at the surrounding areas and the structures around the structure,” Mr. Plasencia said.

The storm also put a much more increased emphasis on data quality and understanding loss mitigation efforts, said Mr. Junge of Swiss Re.

“That understanding of how those physical loss mitigation changes actually should flow through in financial terms into insurance modeling, I think that that can all be traced back to Andrew,” he said.

[ad_2]

Source link