[ad_1]

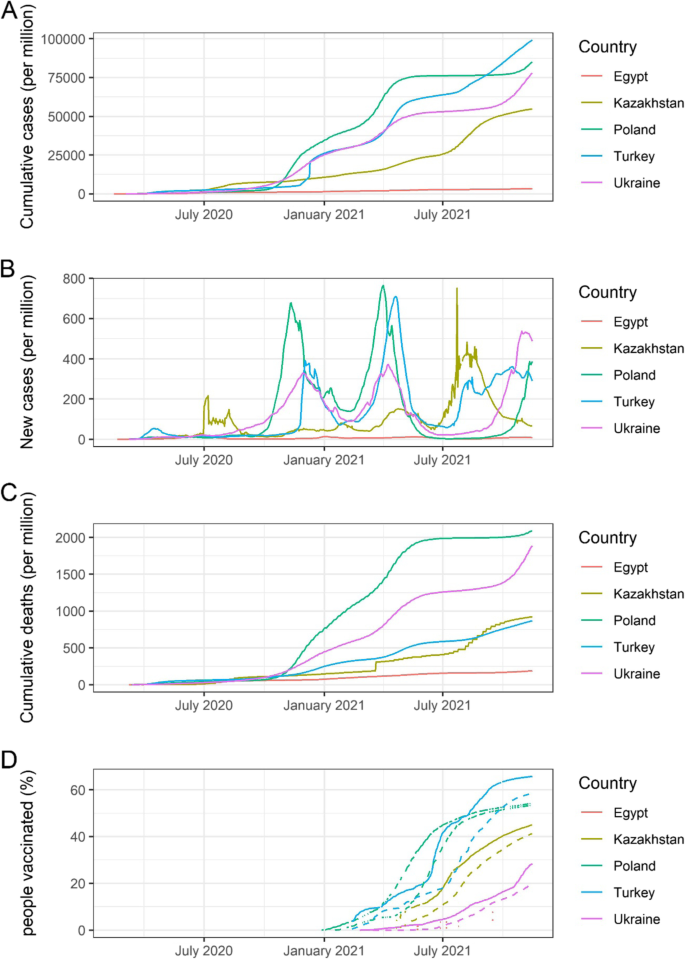

All five countries confirmed the first COVID-19 case in their respective countries between February and early March 2020. Most of the first cases were imported from Western Europe. Turkey, Ukraine and Poland have a relatively large number of cumulative cases (8.4 million, 3.2 milion, and 3.2 million), while Egypt and Kazakhstan have a smaller number of cumulative cases (0.3 million and 1.0 million) as of 16 November 2021 [10]. Cumulative cases, new cases, cumulative deaths, and vaccination coverage in Turkey, Egypt, Ukraine, Kazakhstan, and Poland from 1 February 2020 to 15 November 2021 are shown in Fig. 2. The number of cases, deaths, and vaccination coverage, as well as key health indicators by country, are summarised in Table 1.

Cumulative COVID-19 cases, new daily cases, deaths, and vaccination coverage since the beginning of pandemic in Turkey, Egypt, Ukraine, Kazakhstan, and Poland. A Cumulative cases per million population in Turkey, Egypt, Ukraine, Kazakhstan, and Poland from 1 February 2020 to 15 November 2021, B New daily cases per million population in each country, C Cumulative deaths per million population in each country, D Percentage of people partially and fully vaccinated in each country. Solid line shows the proportion of total population partially vaccinated (received at least one dose). Dashed line shows the proportion of total population fully vaccinated. Vaccination data in Egypt was not available in majority of the time. Vaccination data in Poland was missing at several time periods. (Data source: Our World in Data [11] – accessed on 16 November 2021)

Trends in the observed numbers of cases similarly had three peaks among five countries, although the peaks of transmission were different (see Fig. 2B). The cumulative number of deaths in Poland and Ukraine (2.09 and 1.78 per thousand population) were higher than in the other three countries (see Fig. 2C) [10].

Health sector preparedness and response

Health system and health finance

The five countries had developed different health systems and health insurance schemes before COVID-19, and health system reforms are ongoing.

Turkey has been implementing health reform initiatives since 2003 [18]. This programme improved governance, health financing, and health service delivery significantly, with heavy investment in health infrastructure [19]. The General Health Insurance Scheme (GHIS), funded by a tax surcharge on employers [20], covers 99% of all inhabitants, including over 3.6 million Syrian refugees. Health services are provided both by public and private sector facilities [19]. The GHIS ensures free treatment for various conditions, such as emergency care, occupational illness, childbirth, and infectious diseases [21]. Their health system transformation enabled the outbreak response to be effective and timely with relatively limited strain on the existing health system and capacity.

The Egyptian healthcare system is funded and managed by governmental, parastatal, and private sectors. The Health Insurance Organisation oversees basic health coverage for 60% of the population [22]. The Egyptian health system was revitalised in 2014 and improved the quality of care, health expenditure, availability, and accessibility of disease surveillance. According to the WHO’s assessment in 2020, Egypt has a solid capacity to respond to the outbreak [22].

Ukraine has the weakest health system in the post-Soviet Union countries [23]. In addition, six years of conflict in east Ukraine weakened it further. Public healthcare is still in transition from the highly centralised health system. Free healthcare is the principle; however, 58% of patients reported having made out-of-pocket payments in 2017 [24]. Unmet healthcare needs are a growing issue in Ukraine [25].

The health system in Kazakhstan is highly centralised, and public health service is dominant. One of the key challenges in healthcare reform is the considerable inequity in health financing per capita among the different geographical areas in the country. Another challenge is that 36% of the health expenditure comes from out-of-pocket payments [26]. Since 2017, all citizens are required to participate in employers’ contributions to the healthcare fund. This measure is expected to boost healthcare spending and generally improve services for patients [27].

The National Health Fund finances the healthcare system in Poland with the capitation payment system [28]. Citizens pay their health insurance through their employer, which is 9% deducted from personal income and covers core-family members. Healthcare is free for all citizens; in particular, the government is obliged to provide free healthcare to young children, pregnant women, people with disabilities, and the elderly [29]. A challenge in the healthcare system in Poland is that out-of-pocket expenditure accounts for more than 20% of health expenditure. The number of medical workers per 1,000 population is lower than the European Union (EU) average, while spending for prevention is less than half of the EU average.

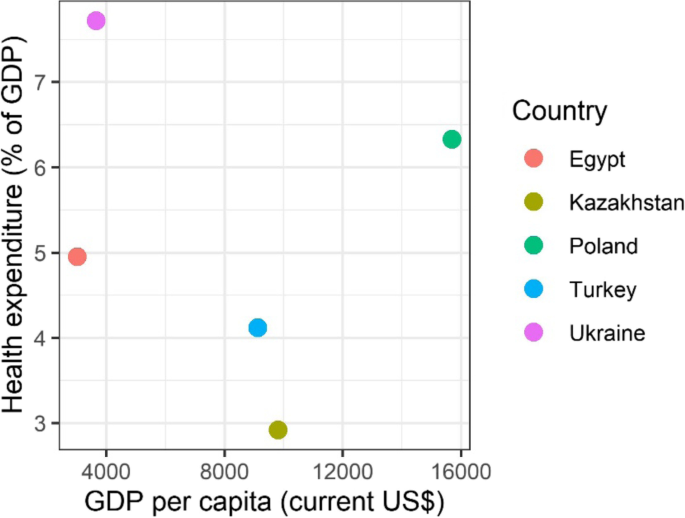

The healthcare expenditure (percentage of GDP) plotted over GDP per capita for the five countries show that the economy and health investment in each country varied (Fig. 3) [16]. Healthcare expenditures per GDP in Egypt, Turkey, and Kazakhstan was lower than 5%, which is below the recommended level of health financing. Although GDP in Poland was at the same level as for other EU countries, the health expenditure stayed low (6.2%), which may partly explain that the life expectancy in Poland is five years shorter than the EU average [30]. Ukraine has the highest health expenditure per GDP, and its health infrastructure and human resources are among the highest levels in Europe. However, Ukrainian medical care might not have met the standard of care in Europe, and their life expectancy is nine years shorter than the EU average (Table 1) [25].

Health expenditure as percentage of GDP versus GDP per capita in 2019 for Turkey, Egypt, Ukraine, Kazakhstan, and Poland. The figure shows the relationship between GDP per capita (current US$) and health expenditure as percentage of GDP in Turkey, Egypt, Ukraine, Kazakhstan, and Poland. Among the five countries, health expenditure in terms of percentage of GDP is relatively lowest and highest in Kazakhstan and Ukraine respectively. (Data source: World Bank Database [16])

National coordination of COVID-19 response activities

Turkey established an emergency operations centre immediately after the confirmation of COVID-19 in China and coordinated response activities through a Whole-of-Government approach. Turkey also established a scientific advisory board in the early stages [19, 31]. The Ukrainian government set up the Health Emergency Operation Committee in the MoH on 24 January and an inter-sectoral working group on 25 April 2020. Kazakhstan created an interdepartmental commission under the government to coordinate activities to prevent the spread of COVID-19 with all related ministries on 27 January 2020 [13].

COVID-19 testing capacity

Generally, probable cases and contacts with confirmed cases were tested by PCR in the five countries. The WHO has noted well-established COVID-19 surveillance systems in Turkey and Egypt [19, 22]. Case definitions of probable and confirmed cases were slightly different by country, though they follow WHO or the European Centre for Disease Control guidelines.

The five countries have made an effort to increase testing capacity during the pandemic. Turkish PCR testing capacity, one of the highest in the world, is supported by 453 laboratories, while Egypt established 40 laboratories [19, 22]. Ukraine had 96 test centres as of November 2020. PCR tests were conducted in nine laboratories at the oblast level and a national reference laboratory in Kazakhstan as part of the influenza surveillance programme. In Poland, 276 laboratories were carrying out testing at the end of January 2021. Total testing capacity exceeded 150,000 per day in Turkey, over 80,000 per day in Poland, and around 50,000 per day in Ukraine as of April 2021 [13].

Information about the implementation of contact tracing was largely absent except in Turkey. Turkey has more than 100,000 field teams conducting contact tracing [19, 22]. Potential contact persons were remotely monitored by audio or video call, if possible, in Kazakhstan [13].

Health infrastructure

The five countries rapidly increased the bed capacities to accommodate COVID-19 patients with the onset of the pandemic. Turkey has 563 hospitals dedicated to treating COVID-19 cases as of November 2020; up to 1,200 hospitals partly provided the care for COVID-19 cases. Over 25,000 ICU beds have already been available in Turkey. In addition, Turkey built two new pandemic field hospitals with a capacity of 1,000 beds [13]. Egypt has 750 COVID-19 designated hospitals with 35,152 beds, 2,218 ventilators, and 3,539 critical care beds. Ukraine increased the available beds for COVID-19 patients from 12,000 at the beginning of the pandemic to 53,445 in 582 designated hospitals as of 24 November 2020. In Kazakhstan, a mobile hospital in Nur-Sultan was assigned to deal with COVID-19 patients exclusively. Poland prepared at least one dedicated hospital in each province for case management [19, 22, 32, 33]. As of October 2020, approximately 8,000 beds and over 800 respirator beds were prepared in Poland [13].

The number of hospital beds in each country before the pandemic is summarised in Table 1. The number of tests, hospitals, and beds after the pandemic as of April 2021 is summarised in Table 2.

Healthcare workforce

Maintaining the healthcare workers for routine health services and COVID-19 responses was the largest challenge in the five countries. The strategies to keep the workforce in five countries were task shifting, financial incentives, and providing psychosocial care for them.

In Turkey, medical and dental residents were repurposed for the COVID-19 response. Poland mobilised non-specialised personnel, retired persons, medical students, and soldiers and assigned them certain tasks in line with their capacity. Ukraine reserved medical students to be hired as a surge capacity [13].

Turkey, Ukraine, and Poland increased the salary for those who work with COVID-19 patients by 100–300%. In Poland, the income loss was compensated for medical staff who were restricted to work out of their hospitals due to potential contacts with COVID-19 patients. Overtime payments and time off duty were ensured by law. Quarantined or isolated doctors received 100% of their salary in Poland and Ukraine. Turkey and Poland provided accommodation for healthcare workers who did not want to put their families at potential risk of infection [13].

In Ukraine, the MoH required healthcare personnel to pass WHO online courses on clinical management and infection prevention and control. WHO led training at 200 designated treatment hospitals and shared knowledge on COVID-19 treatment measures via video conferencing [13].

Medical supply

Due to the shutdown of factories in China, supply chains were considerably disrupted [34]. Many essential medical drugs were produced in China. Shortages of masks, gloves, and personal protective equipment (PPE) were reported worldwide [35]. Turkey, Egypt, Ukraine, and Poland reported a shortage of PPE in the early stages of the outbreak [19, 22, 36]. Turkey had strategized for the production and stockpile of drugs and PPE at a national level. Ukraine has received more than 65,000 items of PPE from WHO [37]. Poland has joined the EU’s medical equipment procurement mechanism for the purchase of gloves, goggles, face protectors, surgical masks, and clothing [38].

Physical distancing and non-pharmaceutical interventions

The five countries imposed regional or national quarantines, “lockdown” measures, between March and May 2020, and gradually lifted them in June 2020 or later. Business offices, restaurants, retail shops, and entertainment venues were closed. Public entities, parks, and beaches were closed. Mass gatherings and religious worship were generally prohibited [19, 22, 23, 33, 39]. Egypt has banned the two largest religious events in the country [22].

In Turkey, curfews have been imposed on those who have chronic illnesses or are aged either over 65 or under 20 years [19]. In Egypt, a night-time curfew was put in place, but no day-time lockdown was imposed [22]. The “partial lockdown” was later questioned because the lockdown period was prolonged without adequate suppression of disease transmission.

Ukraine, Kazakhstan, and Poland took strict restriction policies for all citizens. Ukraine and Poland divided countries into red, yellow, or green zones according to their local epidemic status [13]. Ukraine and Kazakhstan prohibited domestic travel from crossing regional borders as well as international travel [23, 33, 39]. This measure is called an “interstate lockdown,” which restricted the movement of people in a larger area than at household or individual level.

International travel was prohibited partially or fully in the five countries. Negative PCR results were required before entry, and travellers were quarantined at the border.

Health communication

Clear and transparent communication with the public is an important part of the pandemic response and for avoiding panic and misinformation, which may impinge on effective response activities. The official websites, online streaming, and social media became the main communication channels during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The MoH in Turkey established a public website and updated the number of cases and other information, e.g., guidelines, posters, and Q&A (questions and answers). Turkey used social media, including Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram accounts, to share information with the public. In Ukraine, an official recommendation of hand hygiene and respiratory etiquette was posted on several social media channels and the MoH website. Regular short daily briefings about the COVID-19 response were arranged and streamed online on the MoH website and television. Weekly briefings about the COVID-19 situation were distributed by text message or video. In Kazakhstan, visual posters were put at borders or transportation stations, and loudspeakers and mass media were used to disseminate COVID-19 prevention measures to the public regularly. In Poland, information was transmitted by website, Twitter, and Facebook through the official account of MoH or the Primary Health Office. A chatbot on the WhatsApp application also provided information about COVID-19.

Digital communication played a primary role in mass communication during the pandemic in Turkey, Ukraine, and Poland. Their investment in digital health had started prior to the pandemic.

Impact on non-COVID-19 health services

Healthcare access to non-COVID-19 services, including essential health services, was reduced by both demand-side and supply-side constraints. In Ukraine, 14% of households could not access healthcare during the pandemic due to busy hospitals, shortage of medication, suspension of regular services, and lack of transportation [40]. In Poland, despite the significant growth of telemedicine, the total volume of services provided at primary care centres between March and November 2020 decreased by 9.6% compared with the same period of 2019 [33]. Home visits by midwives were minimised, and school nurses had no duties as schools were closed [33].

Telemedicine was promoted in Turkey, Ukraine, Kazakhstan, and Poland to maintain essential health services [13]. Ukraine, Kazakhstan, and Poland continued to provide routine medical assistance to pregnant women and children, patients receiving cancer treatment, as well as other life-threatening diseases while suspending routine screening or examination.

A hotline was created in Turkey, Ukraine, Kazakhstan, and Poland for COVID-19-related consultation or screening. These four countries provided free healthcare services related to COVID-19, including testing, treatment, and vaccination [13].

Turkey, Ukraine, and Poland reduced the number of admissions to the hospital, especially for elective surgery, though they continued to offer emergency surgery. Poland tentatively stopped routine childhood vaccination, though it resumed in April 2020. Ukraine observed a significant declining trend of routine vaccination in March–April 2020, but performance improved by July 2020 [13].

In Poland, training for resident doctors was stopped at the hospitals dedicated to COVID-19 patients. Some doctors in those hospitals have left their jobs as they could not continue their specialized practice, despite their salary being increased by the governmental compensation. There is a concern that the function of these hospitals might not be maintained even after the COVID-19 pandemic [13].

Impact on the economy

COVID-19 is the biggest challenge that the global economy has experienced in the post-Second World War era. Because of the lockdown measures taken, domestic consumption declined by 40% in Kazakhstan [41]. Except for Turkey, the annual GDP growth rate declined in 2020 in comparison to the previous year for Egypt, Ukraine, Kazakhstan, and Poland (Table 3) [40,41,42,43,44]. Despite the well-diversified economy with advanced digitalisation, Poland experienced the first output contraction for over 20 years [44].

Unemployment increased in Egypt, Ukraine, and Poland [40, 44, 45]. The number of people living below the poverty line (US$ 5.50 per day for middle-income countries) increased in Turkey by 1.6 million, in Egypt by 0.2 million, in Ukraine by 2.7 million and in Kazakhstan by 1.1–1.5 million (Table 3) [40, 42,43,44].

Emergency funds were established to support domestic enterprises in the five countries to mitigate the economic fallout. Countries took similar measures, such as [41,42,43,44, 46, 47]: (i) affordable bank loans at discounted interest rates for businesses, (ii) financial support/cash transfers to poor households and affected individuals, (iii) support for firms’ payments such as short-term working capital or unpaid leave or subsidised salaries, and (iv) exemption from tax or social contributions, tax deferrals and subsidised loans for firms or targeted sectors.

These government policies have supported the economy to stay afloat, while Turkey and Egypt faced high inflation [42, 43]. Kazakhstan’s inflation was first driven by increased food prices, but later, the weak external demand, low oil prices, and subsequent exchange rate depreciation led to higher inflation [41]. The impact on the economy and its mitigation measures in each country are summarised in Table 3.

Impact on education, gender, and civil liberties

The COVID-19 pandemic has negatively affected education for children. Schools were closed completely in the five countries for between 19 and 49 weeks as of 16 November 2021 [3]. E-learning or remote learning, such as video-based instruction, matching the skills of the teaching force to the new range of tasks and activities, could enhance the performance of schools. However, distance learning was challenging due to limited access to digital technologies in the five countries. The refugees and migrants in Turkey and Ukraine and general students in Kazakhstan have reported significant problems with the infrastructure of the internet [48,49,50,51]. Therefore, modified schooling and a better social security system were also warranted.

In Turkey, women have been more likely to lose their jobs and carry out domestic labour besides working remotely during the pandemic [4]. Uneven division of household labour by gender has continued or even aggravated. In Ukraine, women are disproportionately affected by the disease because women account for 82% of all health and social workers compared with the 70% worldwide average [40]. The pandemic and lockdowns have also led to an increase in domestic violence by 30% in Ukraine [40].

The shortage of PPE imposed a high risk of infection on healthcare workers. Medical professionals who pointed out the shortage of PPE and training for themselves were arrested in Egypt. Over 70 people, including health workers, journalists, and lawyers, were detained in Egypt between March and June 2020 [52]. One-sixth of the COVID-19 infections occurred in medical professionals in Poland as of April 2020. The Ministry of Health in Poland tried to prevent medical personnel from commenting on the pandemic regarding the shortage of PPE [36]. Censorship of speech in Egypt and Poland has highlighted the importance of balancing public health measures and civil liberties [36, 52].

COVID-19 vaccination

Various types of COVID-19 vaccines have been rolled out globally, including 23 vaccines in different countries, of which eight have been approved for use by WHO (as of 15 November 2021) [53, 54].Turkey and Poland primarily used the vaccine made by Pfizer in the United States of America, Egypt used the Sinopharm vaccine from China, Ukraine used the Astra Zeneca vaccine made in India, and Kazakhstan used the Sputnik V vaccine from Russia. In Turkey, Poland, and Kazakhstan, 66%, 54%, and 45% respectively of the total population have received at least the first dose as of 15 November 2021. On the other hand, in Egypt and Ukraine, only 20% and 28% of the population have completed the first dose as of 15 November 2021 (Table 1, Fig. 2D).

Vaccine hesitancy in communities poses serious challenges in achieving adequate coverage. Ukraine and Egypt reported high vaccine hesitancy in both the general population and among healthcare professionals [55, 56]. The underlying causes of vaccine hesitancy were reported to be the lack of trust in the government-led healthcare sector in Ukraine [55]. Egyptian medical students mentioned that a lack of information about the adverse effects of the vaccine was the primary reason for vaccine hesitancy [56].

[ad_2]

Source link