[ad_1]

This article was produced Reveal from The Center for Investigative Reporting, which is a nonprofit investigative newsroom. Sign up to get their investigations emailed to you directly.

Over the last two presidential election cycles, True the Vote has raised millions in donations with claims that it discovered tide-turning voter fraud. It’s promised to release its evidence. It never has.

Instead, the Texas-based nonprofit organization has engaged in a series of questionable transactions that sent more than $1 million combined to its founder, a longtime board member romantically linked to the founder, and the group’s general counsel, an investigation by Reveal from The Center for Investigative Reporting has found.

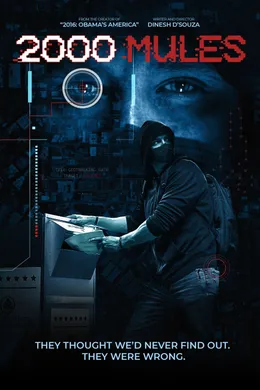

A former PTA mom-turned-Tea Party activist, True the Vote founder Catherine Engelbrecht has played a pivotal role in helping drive the voter fraud movement from the political fringes to a central pillar in the Republican Party’s ideology. Casting herself as a God-fearing, small-town Texan, she’s spread the voter-fraud gospel by commanding airtime on cable television, space on the pages of Breitbart News, and even theater seats, as a new feature film dramatizing her organization’s exploits, “2000 Mules,” plays in cinemas across the country.

Along the way, she’s gained key allies across the conservative movement. Former President Donald Trump, who shouts her out by name during rallies and held a private screening for the film at his Mar-a-Lago resort, exploited the group’s declarations to proclaim that he won the popular vote in 2016. Provocateur Dinesh D’Souza partnered with Engelbrecht on the film. And she’s represented by the legal heavyweight James Bopp Jr., who helped dismantle abortion rights, crafted many of the arguments in the Citizens United case that revolutionized campaign finance law, and was part of the legal team that prevailed in Bush v. Gore.

A review of thousands of pages of documents from state filings, tax returns, and court records, however, paints the picture of an organization that enriches Engelbrecht and partner Gregg Phillips rather than actually rooting out any fraud. According to the documents, True the Vote has given questionable loans to Engelbrecht and has a history of awarding contracts to companies run by Engelbrecht and Phillips. Within days of receiving $2.5 million from a donor to stop the certification of the 2020 election, True the Vote distributed much of the money to a company owned by Phillips, Bopp’s law firm, and Engelbrecht directly for a campaign that quickly fizzled out.

Legal and nonprofit accounting experts who reviewed Reveal’s findings said the Texas attorney general and Internal Revenue Service should investigate.

“This certainly looks really bad,” said Laurie Styron, executive director of CharityWatch.

And while the claims of widespread fraud in the 2020 election have been dismissed out of hand by courts and debunked by audits, even those led by Republicans, the story of True the Vote highlights how exploiting the Big Lie has become a lucrative enterprise, growing from a cottage industry to a thriving economy.

The records show:

- True the Vote regularly reported loans to Engelbrecht, including more than $113,000 in 2019, according to a tax filing. Texas law bans nonprofits from loaning money to directors; Engelbrecht is both a director and an employee.

- Companies connected to Engelbrecht and Phillips collected nearly $890,000 from True the Vote from 2014 to 2020. The largest payment—at least $750,000—went to a new company created by Phillips, OPSEC Group LLC, to do voter analysis in 2020. It’s unclear whether OPSEC has any other clients; it has no website and no digital footprint that Reveal could trace beyond its incorporation records. The contract, which one expert called “eye-popping” for its largess, did not appear to be disclosed in the 2020 tax return the organization provided to Reveal.

- True the Vote provided Bopp’s law firm a retainer of at least $500,000 to lead a legal charge against the results of the 2020 election, but he filed only four of the seven lawsuits promised to a $2.5 million donor, all of which were voluntarily dismissed less than a week after being filed. The donor later called the amount billed by Bopp’s firm “unconscionable” and “impossible.”

- The organization’s tax returns are riddled with inconsistencies and have regularly been amended. Experts who reviewed the filings said it makes it difficult to understand how True the Vote is truly spending its donations.

In one instance, True the Vote produced two different versions of the same document. A copy of the 2019 tax return Engelbrecht provided to Reveal does not match the version on the IRS website.

The IRS version showed Phillips as a board member. Englebrecht’s version did not. The IRS return showed Engelbrecht had a loan balance of $113,396. Engelbrecht’s version indicated the loan’s balance was gone. In response to questions from Reveal, Engelbrecht said she was going to submit an amended version of the group’s 2019 tax return—the one she’d provided to Reveal—to the IRS.

Catherine Engelbrecht of True the Vote.

Gage Skidmore

Engelbrecht declined to be interviewed for this story, routing specific inquiries through Bopp and her accountant. Bopp wouldn’t answer questions about the loan and who approved the contracts, saying that was confidential financial information. He said there was “nothing inherently wrong or improper with contracting with board members to do services for the corporation.”

“I’ve represented not-for-profits for 45 years,” Bopp said, “and it is common.”

However, experts questioned whether True the Vote had the proper structure and policies to safeguard against self-dealing the way other nonprofits would.

As True the Vote has gained prominence, Engelbrecht has maintained an oversized control of the charity as its only employee in recent years and a member of a small board of directors that’s been packed with potential conflicts of interests. “That’s a real problem,” said Styron, of CharityWatch.

The federal government grants nonprofit organizations a special status, allowing them to operate tax-free in recognition of their public benefit. In exchange, they are subject to greater scrutiny and transparency to ensure that donor funds are being used properly.

Experts said an organization with more than $1 million in revenue typically would have more employees and a larger board. “These are public dollars, and the board members and officers of a charity have a fiduciary duty to…spend all of the resources of the charity carrying out the mission of the organization to the best of their ability in ways that benefit the nonprofit,” Styron said. “Not in ways that benefit them personally.”

Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton has appeared on Engelbrecht’s podcast and has been an active supporter of attempts to overthrow the 2020 election. In court filings in a donor lawsuit against True the Vote, his office said it would review the case to see if any action is warranted. Reveal sought his office’s communications about True the Vote through Texas public records law, but he refused to disclose them, citing attorney-client privilege.

Meanwhile, True the Vote’s work continues to get airtime in Trump’s speeches. At a rally earlier this year in Southeast Texas, the former president celebrated Engelbrecht as a champion.

“What a job she’s done, thank you, thank you, Catherine,” Trump said. “If you have any information about ballot harvesting in your state, call Catherine Engelbrecht.”

In the late 2000s, Engelbrecht was a small-business owner in Southeast Texas who was not deeply involved in politics. But Barack Obama’s election as president in 2008 concerned her enough that she got active in local Tea Party efforts, attending rallies and meetings.

Along with her then-husband, Bryan Engelbrecht, she created a nonprofit called King Street Patriots, which trained volunteers who ended up poll watching in mostly Black and Latino neighborhoods in Harris County. It ran into problems for violating the law that prohibits nonprofits from being overtly political, and the Engelbrechts spun off True the Vote.

Catherine Engelbrecht earned regular appearances on Fox News, where she once offered a $1 million bounty for testimony. She advocated for Texas’ strict voter ID law in 2013. A year later, Engelbrecht and her husband filed for divorce and Bryan Engelbrecht left True the Vote’s board. Gregg Phillips, a longtime conservative operative, took his seat.

Gregg Phillips on CNN.

Phillips had been dogged by allegations of financial impropriety, accused of leveraging his government positions in Mississippi and Texas to make himself money. The same year Phillips joined True the Vote’s board, the nonprofit began to pay entities he controlled.

In 2014, True the Vote paid $25,000 to American Solutions for Winning the Future for a “donor list rental.” Phillips was the director, records show. The next year, True the Vote gave $30,000 to a company called Define Idea Inc. for “IT support services.” Phillips was a director of the company, according to its formation documents.

That year, Engelbrecht began receiving questionable payments from True the Vote as well.

According to its 2015 tax filings, it issued Engelbrecht a $40,607 loan. Under Texas law, nonprofit directors can’t receive loans, though employees can. Engelbrecht is both a director and an employee. True the Vote wouldn’t answer questions about who approved the loan, its conditions and whether Engelbrecht voted on it as a board member.

“I’m not going to respond to you on this,” Bopp said. “If you want free legal research, go pay a lawyer to do it.”

But that wasn’t the only way Engelbrecht got access to her nonprofit’s coffers. ARC Network LLC and Ao2 LLC were paid a total of $82,500 in 2015 and 2016 for “database license fees” and “software license fees,” respectively, according to the tax filings, which disclose that the companies are tied to Engelbrecht. Court filings indicate that she owned 100% of ARC Network; she is listed as the owner of Ao2 in registration documents in Wyoming.

ARC Network and Define Idea were barred by Texas in 2015 from doing business, state records show.

A business can be forfeited when a company doesn’t file a mandatory annual report showing its owner, directors and registered address—or when it does not pay taxes. Reveal couldn’t find other clients or a footprint for the two companies Engelbrecht owned.

Brian Mittendorf, an Ohio State University accounting professor who specializes in nonprofit accounting, said the records raise a series of red flags.

“We always have concerns from a governance standpoint about organizations engaging in such transactions with insiders, and the organization’s behavior, in terms of its accounting and inconsistencies, only inflame those concerns,” he said.

Engelbrecht and Phillips’ ties go beyond True the Vote. Their companies have shared the same mailing address, and Engelbrecht in 2016 was named the CFO of one of Phillips’ companies. In court filings, a donor later alleged that the two were “lovers,” something they haven’t denied.

When Reveal asked Bopp about their relationship, he said: “I do not know the facts because it’s none of my business, whether they’re in a romantic relationship or not.”

In 2016, just weeks after pulling off his stunning presidential victory, Trump made an unprecedented claim: Millions of people had voted illegally in the election. And, he said, that’s why he’d lost the popular vote to Hillary Clinton—by what would ultimately be about 2.9 million votes.

He didn’t offer up any evidence. But weeks later, Phillips appeared on CNN claiming he had the data analysis to show that more than 3 million voted illegally in the 2016 election. But when asked to show proof, Phillips said he needed time to verify the data.

“(We) believe that it will probably take another few months,” Phillips said.

Trump tweeted shortly after the interview: “Gregg Phillips and crew say at least 3,000,000 votes were illegal. We must do better!”

True the Vote quickly used the opportunity to push a $1 million fundraising campaign to audit its data.

“Our audit team will include world-class technologists, researchers, data miners, statisticians, scholars, analysts, and subject matter experts. This isn’t B team stuff,” Engelbrecht wrote in a fundraising email. “The integrity of our election is too important.”

But Engelbrecht and Phillips never completed the audit or released the evidence behind their claims. In a video posted on YouTube in June 2017, Engelbrecht said they dropped the effort because donor promises didn’t materialize.

In 2017, the organization was in the red by more than $139,000. It reported having one employee, Engelbrecht, down from 11 employees in 2012. The $40,607 loan to Engelbrecht remained on the books in 2017, accounting for more than 66% of the nonprofit’s total assets.

The next year, True the Vote reported it had $4,754 in cash.

But that didn’t stop True the Vote from giving ever-growing loans to Engelbrecht. In 2018, it disclosed an outstanding $61,896 loan to Engelbrecht. It’s unclear whether Engelbrecht took one loan that grew over the years or multiple loans.

The nonprofit’s tax returns make it difficult to follow.

Lloyd Mayer, a nonprofit law professor at the University of Notre Dame, said there’s “a lot of sloppiness” in the financial statements. Documentation around Engelbrecht’s loan at times contradicted itself, saying in one section she paid it off but then still had a balance in another.

“The changes over time and the fact that in 2017, it doesn’t say which way the money’s flowing, would make me ask if I was in the attorney general’s office, at least ask: Could you clarify?” Mayer said.

In a number of years, True the Vote never answered important governance questions in its tax filings, such as whether it has policies around conflicts of interest, whistleblowers, document retention, and how it determines Engelbrecht’s pay. “Importantly, it fails to answer questions about family or business relationships between officers and board members,” said Styron, the leader of CharityWatch. She called True the Vote “a governance black hole.”

It’s also unclear when Phillips left the board. In court documents, he says he left the board in 2017. However, the 2018 tax return listed him as a board member, as did the original 2019 filing. Phillips didn’t respond to multiple attempts to reach him for comment; he has previously denied wrongdoing in the Mississippi and Texas cases.

When True the Vote claimed it filed an amended 2019 return in response to Reveal’s questions, it filled in the governance questions and no longer listed Phillips as a board member. Experts said the differences in the amended return were highly unusual.

“To me, that makes no sense,” said Philip Hackney, a former IRS official who teaches tax law at the University of Pittsburgh.

As the November 2020 election approached, Engelbrecht and attorney James Bopp Jr. warned on the nonprofit’s podcast that Democrats planned to use the courts to expand mail-in voting and said the organization had a plan to challenge it.

“We’re going all in on this,” Engelbrecht said on her show in May 2020. “If you would have asked me two months ago, I would have not told you that litigation was any part of what we plan to do at True the Vote in 2020, but now it’s the most important thing we can do.”

Yet as Election Day neared, conservative leaders were sounding the alarm about True the Vote. During a private meeting of the Council for National Policy in August 2020, a group of panelists was asked what they thought about True the Vote. Conservative journalist John Fund said he was the one who’d given Engelbrecht her first national publicity.

“I like Catherine, but she has gone astray. She has hooked up with the wrong associates. And I have to say this with the greatest of sadness, because I have to be honest with you, because you’re the people who actually have to make decisions on your own about who to support. As much as I like Catherine personally, I would not give her a penny,” he said, according to a recently leaked video obtained by Documented. “She’s a good person who’s been led astray. Don’t do it.”

Soon after, in September 2020, Phillips opened his latest business: OPSEC Group LLC, incorporated in Alabama. It sprang up at the perfect moment: Trump already was casting doubt on the upcoming election’s outcome.

Then Election Day came, and Trump demanded that states stop counting votes as it appeared Biden would win.

He claimed victory, saying—without proof—that he’d been the victim of massive fraud. Trump’s campaign promised action: a legal campaign challenging the outcome in Pennsylvania, Michigan, Wisconsin and Georgia. Rumors and conspiracy theories about illegal voting—often in Democratic areas home to Black and Brown voters—ramped up in earnest.

Fred Eshelman watched in angst. A pharmaceutical entrepreneur from North Carolina, Eshelman was concerned that the election had been riddled with fraud.

A political consultant emailed some of those conspiracies to Eshelman the morning of November 5, according to records filed as part of a lawsuit in rural Austin County, Texas.

Eshelman responded eight minutes later. “This stuff really needs to be verified, quantified, and a massive information campaign launched at American people,” he wrote. “You want a revolt from the Silent Majority, you got it.”

He told the consultant, Tom Crawford, that they needed the best and most powerful public relations firm “cranked up now,” and they had to “figure out how to get it out in spite of the media.”

At 6:36 a.m. that same morning, Bopp emailed Engelbrecht with the urgent plea to call him. The email’s subject line: “voter fraud and a legal challenge.”

“I have been contacted by a friend with access to substantial funding regarding an idea about lawsuits re voter fraud,” Bopp wrote. “You might be central to that. I would like to discuss.”

Within hours, Engelbrecht prepared a donor pitch for what she called Validate the Vote, a litigation plan to challenge the election using data and whistleblower testimony.

The two teams had a brief call, and Eshelman decided he was in. He wired True the Vote $2 million, records show.

True the Votes’ plan laid out the details: Bopp, touted as the lead attorney in Citizens United and Bush v. Gore, would file lawsuits in seven states across the country to “nullify the results of the state’s election so that the Presidential Electors can be selected in a special election or by the state legislature.” OPSEC would “aggregate and analyze data to identify patterns of election subversion.” True the Vote would build public momentum and “galvanize Republican legislative support in key states.” The total cost of the campaign: $7.3 million.

“Thank you for this opportunity. We will not let you down,” Engelbrecht wrote in a November 5 email.

They were off. First, Bopp planned to file lawsuits in Michigan, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania. and Georgia.

But days later, the plan started to show strains. On November 7, the Associated Press called the election for Biden. By then, many lawsuits filed by the Trump campaign started to get dismissed in multiple states. The day after, Engelbrecht sent a text message saying Eshelman wanted to talk about their game plan moving forward.

“He’s getting skittish that we can’t do this because the Trump camp is falling apart and people are jumping ship,” she said.

Still, they pushed ahead and began spending Eshelman’s donation. On November 9, Phillips’ OPSEC submitted a bill to True the Vote for $350,000, according to court records. The invoice for the services is sparse; it bills for “Validate the Vote.” The quantity: one. It includes a litany of items ranging from “data” to “analysis,” “whistleblower” and “security,” all lumped in the six-figure bill.

The next day, True the Vote paid Bopp a $500,000 retainer, according to court records. It also paid Engelbrecht a total of $30,000, the records indicate.

By November 11, Eshelman was getting impatient, according to the communications. He wanted to know what the team was uncovering through its state-of-the-art computer programs and whistleblower tip line.

“I know you’re running very hard, and I don’t want to pile on. However, I do want to know what money is accomplishing, where this is headed and the odds of winning,” he wrote to Engelbrecht.

But Eshelman began to question the team as he failed to get the concrete follow-ups he expected from Engelbrecht.

“I cannot continue to spend millions if this is quixotic,” he wrote to Engelbrecht and the consultant, Crawford, the morning of November 11.

He saw an analogy in his own work that could be applied to his new calling. It was similar to a drug development process: Get the technology and then get the hard data to support the claims. This wasn’t “rocket science,” he wrote to Crawford. True the Vote said it had both handled.

By the end of that week, Engelbrecht said she needed more money for the project, according to court records. The $2 million hadn’t been enough. The consultant told Eshelman that they may need “additional short-term money for Bopp.” Eshelman wired another $500,000 on November 13.

The next day, Engelbrecht touted knowledge of four whistleblowers but never identified who they were. When the consultant followed up with Engelbrecht later to get details on the whistleblowers, it led to tension.

“I just had a difficult call with Catherine,” Crawford wrote to Eshelman on November 15. “She is resistant to sharing ANY details with us about whistleblowers or the data work and took an ‘I run this’ tone with me.”

That day, Eshelman implored Engelbrecht again to share whatever information she had on data and whistleblowers for the lawsuits so he could send it to South Carolina Sen. Lindsey Graham and Crawford, who’d said earlier that he had Fox News’ Sean Hannity waiting to break the news.

The consultant updated Eshelman that Graham’s team was “growing more skeptical every hour that passes with nothing from Catherine.” And he shared what he said Cleta Mitchell, an attorney aiding Trump’s attempts to overturn the election, thought of Engelbrecht.

“Again, I am sorry for this headache. Cleta Mitchell, a well-known election attorney called to cheer us on for helping Bopp and told me Catherine ‘is crazy as a shithouse rat,’ ” Crawford wrote to Eshelman.

(Mitchell, who had once represented True the Vote, denied ever making that comment. “I’ve never used that term in my life,” she said in an email to Reveal. “I’ve got lots of colloquialisms. That isn’t one of them.”)

On November 16, True the Vote convened a conference call with Eshelman and his consultant. The big donor learned that the group had voluntarily dismissed the four lawsuits. Emails show Eshelman was furious about the decision.

“I cannot believe they did this without giving us a chance to get to Trump or be in on the decision,” Eshelman wrote later that day to his consultant, according to records.

“Very frankly I was physically sick after our call,” Eshelman wrote to Engelbrecht. “I have to tell you this is a total disaster from a coordination, communication, and representation perspective.”

By that point, True the Vote had spent one-third of Eshelman’s gift in 11 days and failed to produce anything meaningful in evidence, the records show.

In an email to Eshelman and Bopp following the meeting, Engelbrecht indicated they fell short of funding goals. She told them that “our not having full funding was well known and often discussed.” She mentioned that she assumed the Trump campaign would be pitching in.

“I’d written in my 11/14 email to you that it appeared our legal fees would have been covered by the Trump campaign, which I described in a statement of our cash position, described as best possible given the tight timeline with so many moving parts,” Engelbrecht wrote in a November 16 email.

Later that night, Crawford began to express regrets about going with True the Vote. He told Eshelman he had been told that Bopp “was the guy” they needed for the legal efforts.

“To get him I had to go through True the Vote. Given timing, I ran with that and am just kicking myself as it is clear from many friends and insiders that Catherine is a disaster,” Crawford wrote to Eshelman. “Her story is utter Bullshit.”

Eshelman ultimately sued the nonprofit in federal and state court, accusing True the Vote of using his donation to enrich Engelbrecht, Phillips, and Bopp. In court filings, True the Vote argues that Eshelman wasn’t entitled to his money back because there were no strings attached to the donation and that the relationship became strained after True the Vote didn’t want to pay a $1 million invoice connected to one of Eshelman’s consultants for communications. (The federal suit was withdrawn. In the state suit, True the Vote argued that the court didn’t have jurisdiction to handle the dispute, saying it was the purview of the Texas attorney general, Ken Paxton. A judge agreed and threw out the case. Eshelman has appealed the decision.)

In a recent deposition in a separate lawsuit, Engelbrecht admitted that True the Vote had not identified widespread voter fraud at the time she pitched the Validate the Vote plan to Eshelman, despite proclaiming there was “significant evidence” in the one-page proposal she emailed to him on the project.

“This was a promotional piece,” Engelbrecht said of the document during the deposition, according to court records.

Presentation in Wisconsin.

Courtesy WKOW

Bopp never served on True the Vote’s board and doesn’t face the same potential conflicts of interest as Engelbrecht and Phillips do for some of their transactions, but he has come under scrutiny for the amount he billed for the aborted legal campaign.

In the court records, Eshelman’s team said Bopp’s firm billed for more than $183,000 over a five- to seven-day period, in addition to more than $97,000 to supervise those attorneys.

“After spending in excess of $280,000 to draft and file the nearly-identical complaints in those cases, Mr. Bopp and his law firm then dismissed them all just days later,” the lawsuit reads. “Not only is the amount charged for these cookie-cutter complaints unconscionable—and likely impossible given the size of his firm (only five attorneys) and the number of hours available—but the goal was actually unachievable.” Eshelman said he later learned that the voter data Bopp sought in the suits would not even have been available before the election results would’ve been certified.

Bopp said there were no cookie-cutter lawsuits – each state had different laws and procedures, requiring lawsuits to be tailored for each. “These people are so ignorant,” he said of Eshelman’s group. “This was ignorance.”

He said he dropped the lawsuits because courts didn’t act on them fast enough for him to acquire voter data.

Bopp said his work was efficient—“remarkably cheap”—and dropping the lawsuits was the financially responsible thing to do. “Why the hell am I being criticized for trying to save my clients money rather than just go forward?” he said. “Knowing that it’s highly unlikely that any of the legal work that I do will bear any fruit whatsoever? I mean, I should be praised for saving the client’s money.”

Rick Hasen, an election law expert at the University of California, Irvine, called the lawsuits “bogus” to begin with. “Jim probably withdrew the lawsuit so that he wouldn’t have to perpetuate a fraud on the court,” he said.

As for the $30,000 payment to Engelbrecht from Eshelman’s donation, Bopp said it was to oversee the project. True the Vote said it was part of her $197,000 annual pay.

And Phillips’ OPSEC continued to bill True the Vote after Eshelman had broken ties, according to court records. On Dec. 7, OPSEC billed the nonprofit for $400,000 for a project called Eyes on Georgia.

At the same time, Phillips and Engelbrecht had another business going. While she reported working full time for True the Vote, Engelbrecht also was the president, according to records, of another software company Phillips owned that had a nearly $800,000 contract with Mississippi’s Department of Information Technology Services.

At the end of 2020, Engelbrecht and Phillips received an extension to the contract. They renamed their company, which promises to detect fraud and abuse in government programs, from AutoGov to CoverMe Services Inc. It is a health care software company.

The company was awarded a nearly $1.7 million contract for work through 2023.

Trump and True the Vote have moved past the failed election lawsuit strategy and are on to the next conspiracy theory: illegal ballot harvesting.

That’s when a third party—like a household member, activist group, or nursing home—collects and submits absentee ballots on behalf of others, which is legal in a majority of states. It may be a new angle for Engelbrecht and Phillips, but they already have a similar refrain.

In an interview with conservative talk show host Charlie Kirk, Engelbrecht and Phillips said they planned to show their evidence following the May 7 launch of the film “2000 Mules.”

The feature film “2000 Mules” dramatizes the exploits of True the Vote.

Wikimedia

“At some point, shortly after the video runs, we are going to pull the ripcord, we are going to release all of this,” Phillips said.

In a scene that mimics a spy thriller, the film’s trailer depicts two characters, who appear to be Phillips and Engelbrecht, making a tension-filled decision to release earth-shattering information.

The film touts part of True the Vote’s new strategy: using anonymized cellphone data sold by vendors to show when a person was near a ballot dropbox multiple times – ostensibly hinting at “ballot harvesting” activity.

Engelbrecht and Phillips still haven’t released the evidence. At one point in the film, they claim to have used the cellphone data to help solve the murder of a young Atlanta girl; that, too, has been debunked.

So far, True the Vote’s cellphone data analysis is not convincing state officials in Wisconsin that illegal votes were cast.

In a hearing in Madison earlier this year, Engelbrecht and Phillips said their analysis suggested people were delivering ballots that weren’t their own.

But again, when asked to show the evidence, they declined.

Reporter Ese Olumhense contributed to this story.

[ad_2]

Source link